Systems are elastic

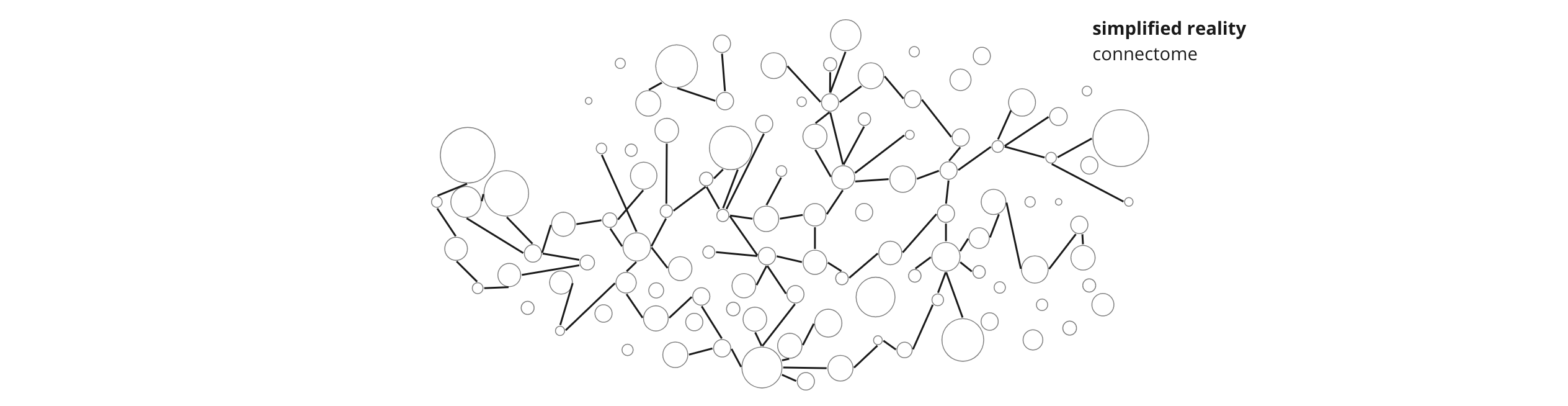

How systems rebalance is through and because of elasticity, and that elasticity in most prevalent in the connectome.

Information is everything. Everything. Our minds, our bodies, our environment, our world, our universe can be understood and shared through information. The most important part of that information is connection. We can’t touch it. Its physical representation is bound up in our node-focused understanding, in unique and (mostly) touchable forms. Connection is how those forms relate. It is borderline ineffable, overwhelming in all the possible connections, and filled with potential.

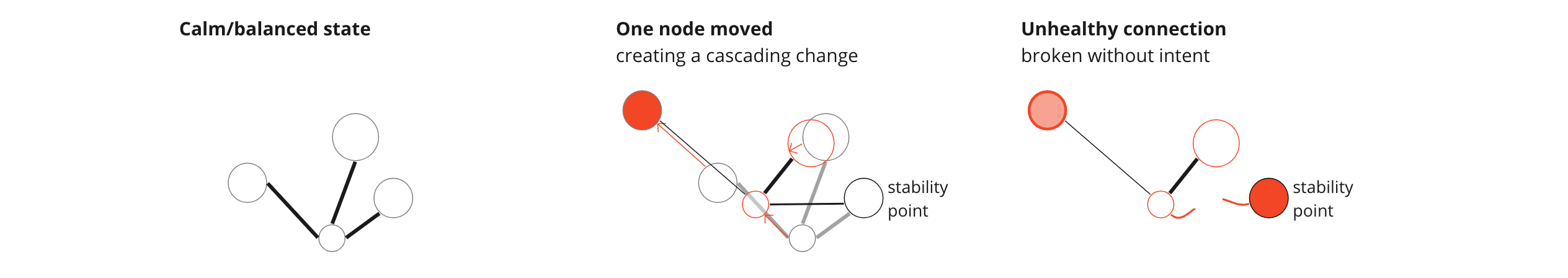

When elasticity is healthy, systems have resilience. When nodes are stressed, the connections stretch and release; sometimes with force, sometimes gently as other system characteristics compensate, softening the return.

But elasticity can fade. Connections can break and rebound, sending a system node into collapse. Disconnecting one node can spark failure in other nodes, sometimes immediately, other times it’s a slow withering. Cascading system failures can be the result of what looked, to current understanding, like a negligible part of the system, barely functioning or connected. The lack wasn’t in the node, but in understanding the connections. We couldn’t suss out ramifications because we didn’t fully understand the context.

Physical model: rubber bands

It’s hard to even describe system elasticity from a distance without thinking about and evoking rubber bands.

Rubber bands are everywhere. They contain bunches of scallions and stalks of broccoli at the grocery store. They get used to keeping long papers rolled and more manageable. Bungee cords are super ones that keep all kinds of things temporarily held together, even when rocketing at speed down a highway. We even exercise with them, using resistance bands to increase the tensile strength of our muscles.

All we need to do to understand elasticity is play with a rubber band. If it’s fresh, some of us can sit and fidget with them for hours. It goes any which way, and it always returns. Fast or slow, it returns. Lose control of it, and it will shoot off in a way that, even as the person fidgeting with it, can be startling.

If it’s been worn or slightly cut? Chances are pretty strong that on a particularly dynamic pull, it will snap.

And if it’s old and unused? No resilience is left at all. Any pull and it will tear easier than paper. No snap, no startle, just…done.

When we’re playing with a rubber band, we’re playing with one force vector. We can move either end in space, the direction is open, and we can swap the stability point or even not have a stability point.

All this is true in a system, too. The difference is that there’s more than one rubber band. There can be infinite rubber bands (connections) to a single node. As that node shifts, the other rubber bands connected to it are activated. Depending on the connection’s health, tensile strength, and attraction to the node connected at the other end, other nodes can shift, too. If a node doesn’t shift, there is more stress on the connection. More elasticity is in play. If the connection isn’t healthy, it can be that one shift, multiple connections away, that can cause a system failure.

Information model: findability

In information architecture, findability is the quality of organizing information so someone can find it. It’s just as much art as science.

All findability is built on a foundation of taxonomy, which is itself predicated on language. What works in English won’t necessarily work, in direct translation, in Korean. But once language and taxonomy are considered, findability boils down to information structures in place along at least one of several potential approaches: navigation (e.g., menus, user flows), search (e.g., process), metadata (e.g., filters, SEO), content (e.g., database cells, written narrative). Each of them depend on the user sussing out information scent, an unstated connection between taxonomy and structure. Some systems will go as far as characterizing the connection to form ontologies, but they are still relatively rare in our built systems. We are much more likely to depend on user knowledge and mental flexibility to align to our models. Good information architecture tries to figure out how people are thinking about particular pieces and designing around that, without getting so precise that it loses information scent outside of the persona. Really good information architecture is also integrating disparate pieces to find a balance in the whole.

I grew up in the midwest. By the time roads and navigation was being built there, as a culture we’d firmly grasped the ease and navigability of grids. Go a block too far? Take two turns right/left, one turn left/right, and you’re back on track.

I also lived for decades in Boston, filled with streets built on legendary cow paths. Winter Street became Summer Street without taking a turn. There were intersections where you could take a hard right, bear right, or bear left. You could start out heading north and, without turning off the street, wind up south. Streets could be so narrow that areas had alternating one-way streets, adding to the complexity of navigation.

The grid layout of the midwest is more akin to focus-built navigation paths: we’re providing structure and rules to set an acknowledged and understood baseline of approach. Boston’s streets are more like search and metadata: to be holistic, the approach can feel a little chaotic, but reorient to big structures — information scent and knowledge — and you can get nearly anywhere, eventually.

The content is where we’re trying to get to, the information in all the density and nuance we want or need to use; yet without that goal, it’s pointless to get into navigation or search. The content still requires its own information structures, and are often leveraged as part of the search and metadata approach.

Any complex information store will leverage multiple findability approaches, even multiples of each type. They are not exclusive of each other, but can be layered to be useful to more minds and knowledge backgrounds.

By interleaving findability, we’re creating dimensional elasticity. Taken as a whole and done well, we can support evolving information and cater to multiple personas. But there’s a pratfall built in: all it takes is one super-connected, too-structured/unweildy/information-scentless/etc. taxonomy list to send it into system collapse.

With information, the three most likely resilience-diminishing qualities are disconnect, controlled flow, and misinformation.

Think of any of our -isms to understand disconnect. Portions of our society have decided that, based on arbitrary characteristics of race, sex, age, disability, etc., a person is no longer a node with relevant perspective. They literally no longer count and lack any meaningfulness. It’s tragic and tragedy-inducing, and it also shuts down entire classes of information possibility.

Think of controlled information as a steady, monoculture news diet from one source alone. If the only diet is Fox News, anger abounds. If the only diet is the Financial Times, everything revolves around financial impact. If the only diet is USA Today, it’s mostly fluff with just enough of the headlines to keep up with others.

Think of all the chaos that happens from misinformation. Whether it’s stale, outright lies, gaslighting, focused on cherry-picked aspects, or a communication gap, misinformation leads decisions and decision-makers astray.

Each of these qualities can stress system connections to the point of cascading failures, rebound, or snap/collapse. Even if every information node is healthy.

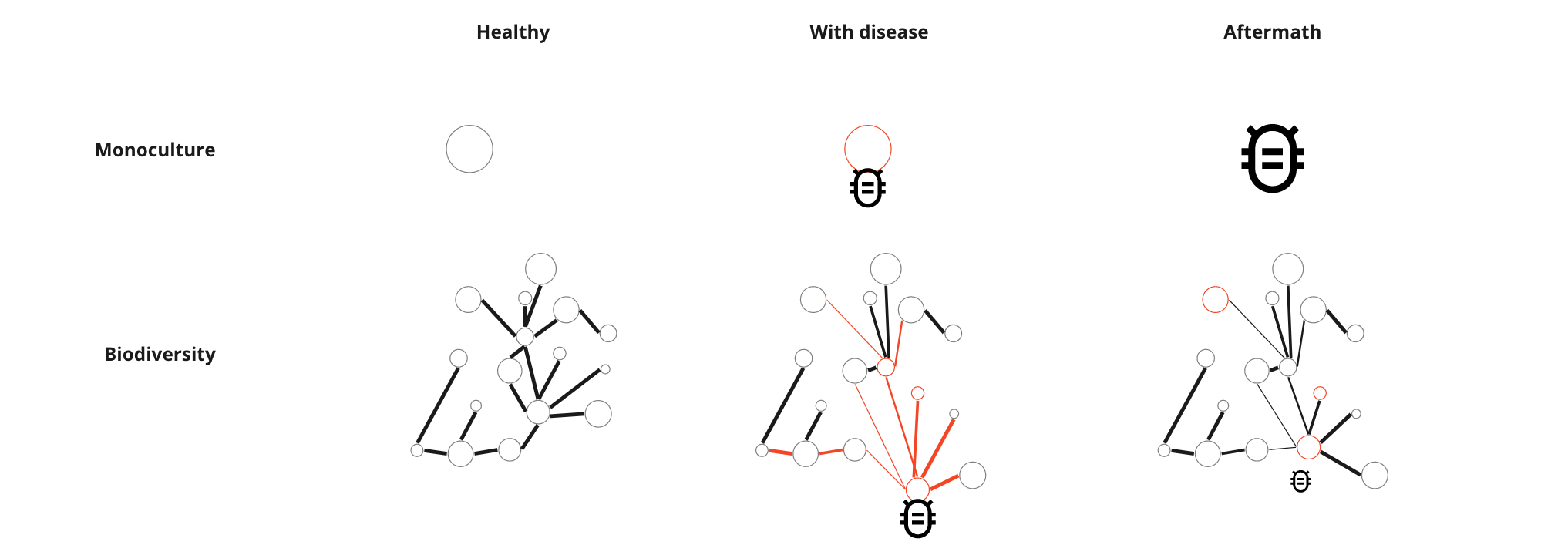

Social model: diversity

Any biologist will tell you that a healthy tract of land has biodiversity. A wild place with an invasive species that is stifling growth and diversity, like kudzu in a forest, is in a slow death spiral towards monoculture. Once an area has a monoculture, all it takes is one insect infestation, virus, fungi, or bacteria to wipe it out.

It’s the difference between a single holistic point, and being able to spread stress out. Devastation can still happen; a weakened system node several steps away could still fail. But the chances of the ecology shifting beyond recognition is far less.

In the monoculture row, there is a simple node under Healthy. Under With disease, a bug is introduced and the node's outline is made red. In Aftermath, there is only a large bug.

In the Biodiversity row, there is a system under Healthy. Under With disease, a bug is introduced, with the affects flowing through the system through the connectome, highlighted by turning the lines red. In Aftermath, there is a smaller bug with a few nodes still outlined in red, but the system as a whole survives.

A simplified way of looking at biodiversity is that is spreads the bets. Like not putting all your eggs in one basket, it makes sure that the inevitable stumble won’t destroy everything.

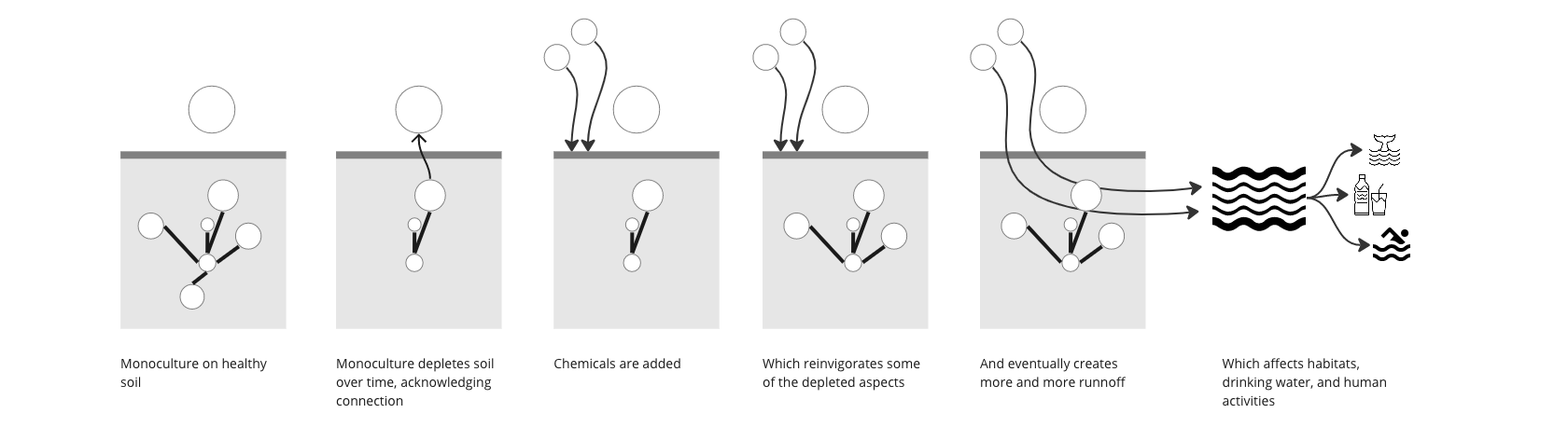

We consistently choose monoculture with our standard farming practices.

Monocultured farmland has incredible yields for a while, and makes harvesting super easy and fast. It also destroys the soil. Over time, with seeds sprouting from unhealthy soil, more and more chemicals are used to support the yield, which creates runoff that can affect adjacent biological and social systems.

The lesson here is that, even if it’s deliberately mentally compartmentalized with no outside connections, the overarching system is still affected. “How affected” is found through the connections, which viewed through systems thinking can build understanding and meaningfulness.

Meaningfulness is invested in every system, provided through the connection and surfaced through context. It is our cognitive dissonance — that expanding space between reality-as-it-functions and reality-as-it’s-seen — that weakens elasticity to the point of breaking. Just like with a rubber band, it can be resilient or it can be on the verge of failure. If it’s resilient, it sees close enough to reality-as-it-functions to make good decisions that impacts the system mostly as expected, and can pivot with surprises. If its on the verge of failure, its so focused on reality-as-it’s-seen that it won’t even acknowledge the damage in its wake.

Even if life itself founders in response through cascading failure, those who focus on the reality-as-it’s-seen perspective can feel the cognitive dissonance and not see system damage. They only have the feeling to go on, and confabulate (that system flow of information in a vacuum) to make sense of it.

Personally, I have a problem solving, puzzle-intensive viewpoint. It’s my lens. I am more invested in reality-as-it-functions than I am in individual people. Yet the puzzle cannot find a balance without also understanding human behavior — or at least the decision making aspect of it, the closest conjunction to information. When I set my problem solving mind on the survival of the species — and we are there — it comes back to our valuations like one of those ball-and-paddle toys.

We have incredible intellectual wealth simply based on our numbers, if we just made education and credibility more accessible. We have an amazing wealth of human energy with which to build, if we just point it in the most useful directions. We have an astonishing wealth of perspective with which to problem solve, if we could just learn to listen to everyone.

With just these three things — an education to build understanding, the energy to make, and multivariate perspective to problem solve — we can fix anything.

Stress any one of these nodes, and problem solving founders. Diminish education, and we just keep testing the same “solutions” infinitely. Stop putting energy into a build, and is simple never gets made. Diminish perspective, and critical thinking dissolves. Diminish resources too deeply, and people don’t survive. Nothing nixes a project harder or with more finality than death.

These are the fundamental nodes to consider to create a world where humanity survives, and a mostly-similar ecology thrives. All four of these qualities — learning, the energy to build, perspective, material resource allocation — go back to information.

The elasticity between nodes in a healthy system can make up for shortfalls; we can do things like find a way to let carbon stay sequestered in growing trees if we put our minds to it. But it means the information structure has to not only function closer to reality, but be seen as something closer to how it functions. By understanding the connections that exist, we can more easily leverage the information structure and see how to rebalance the whole.

In a reality-as-it-functions capacity, each of these four categories have direct connections to each of the other, as well as a multivariate and fungible network from which to draw. In a resilient, understood system we can wittingly compensate for what we have done to our material resources and focus on the abundance of other wealth.

To the left, resource allocation is enlarged and centralized. It connects to each of learning, ergs, and perspective/problem solving. No outlier nodes can share information without going through resource allocation.

To the right, all four nodes are the same size, and all four nodes have direct connections to each of the other threed. Between the two diagrams is an arrow labeled, "shifted to," indicating that it takes a shift to our synthesis of the system to shift our footing.

There was a pratfall built into our current connectome; we’ve super-connected resource allocation. We’ve done this to the point of casting off diverse perspectives, making education a hurdle and a moving goalpost, diminishing the worth of sweat, and filling the connections with misinformation to keep resource allocation on a preconceived stability point, with all other options siphoned through it.

All it takes is a shift in the information structure. But damn, it takes a shift in the information structure. Those are the most time-consuming, anger sparking conversations.

Systems thinking

Systems thinking helps us wrap our heads around the idea that once we understand a network, there’s more happening. I talked about flow, contraction/expansion, and elasticity. I wrote about them singly, but as I work with information, I wobble amongst all of them depending on what I’m trying to make sense of. I don’t think there’s any system that doesn’t respond to all three. While these are the three that have made sense to me, there are probably more.

Our system impacts literally bend the physical world. Our cumulative decisions have created change on a planetary scale. They have wobbled us out of 23 thousand years of a comparatively stable temperature fluctuation. They have wobbled the axis of the earth through shifting groundwater to the surface.

We’ve done it to eat, and drink, and be warm, and not get sick. We’ve done it because we wanted to spend more time with specific people in our lives, and feared death.

We unwittingly changed our world. Most of that change happened due to the cumulative effects of countless decisions, many of which were organized and made easy for others to pick up the end result. This was done by business, government, educational institutions, and religions — social organizations that wrapped up knowledge and served it as a validated checklist to others. They often started out as trying to help people navigate the expansion/contraction states of information, but people are people. Human behavior intertwingled with the information, mostly through mechanisms that impacted the resiliency of the connectome: disconnect, controlled flow, and misinformation.

If we make witting decisions, leveraging systems thinking to the best of our ability, and being willing and able to pivot when new information comes to light, we can keep the world human friendly. We can do this on grand scales, like carbon dioxide removal efforts and stopping the overfishing of our oceans. We can do this on mass-impact scales by working towards ethical, non-traumatizing, and accessible design — the mass-impact ingestion point in our technology. We can do this in our production by expanding to include more edge cases and accepting the breadth of impact in multiple systems. We can do this individually by asking ourselves if we really need this thing and considering the negative impacts as well as the positive. And yes, they will all drastically impact our economic paradigm.

If we can learn to shift the very nature of valuation, the overarching system will rebalance. If we can do it thoughtfully and incrementally, it will rebalance over a series of shifts. If we can only change the system after it’s been pushed to collapse, then there will likely be cascading failures in an environment already on the brink. That’s not a good scenario, purely from the perspective of systems information structures. The probable impact to people is heartbreaking.

People are smart, creative, hardworking creatures. We have questioned our consciousness and found answers. We work, continually, on a plane of existence that we can’t physically touch, but which is informed by a multiplicity of layered physical systems. We have altered our reality, and our planet.

We can figure this out. But we have to choose to change.

bad actors, connections, connectome, context, failing information states, implicit process, information structures, internalized, lenses, meaning, network, nodes, perspectives, reality adhesion, system connectome, system expand/contract, taxonomy